Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

1.

direct insight

Hannah M

What 'direct insight' are other philosophers claiming to have into moral properties?

(This relates to Sinnott-Armstrong et al. (2010, p. 268) rejection of direct insight.)

‘Epistemological intuitionism is the view that certain moral propositions are self-evident---that is, can be know solely on the basis of an adequate understanding of them---and thus can be known directly by intuition’ (Stratton-Lake, 2002, p. 2).

Another case: Audi (2015)

(thanks Paul Theo!)

‘Intuition is a resource in all of philosophy, but perhaps nowhere more than in ethics‘ (p. 57).

‘Episodic intuitions [...] can serve as data [...] ... beliefs that derive from them receive prima facie justification’ (p. 65).

‘self-evident propositions are truths meeting two conditions: (1) in virtue of adequately understanding them, one has justification for believing them [...]; and (2) believing them on the basis of adequately understanding them entails knowing them’ (p. 65).

Hannah M

What 'direct insight' are other philosophers claiming to have into moral properties?

Jagoda’s second question

How does implication 2 (in part 1 of lecture 2, "why is the affect heuristic significant") defend consequentialism?

Consquentialism seems to have counter-intuitive consequences, for example in the Transplant scenario.

Their counter-intuitiveness seems to be an objection to consequentialism. (And they are an objection if we follow Rawls (1999)’s ideas about reflective equillibrium.)

Sinnott-Armstrong et al. (2010) are suggesting that the hypothesis about the Affect Heuristic indicates that our intuitions are reliable only in familiar situations.

Emily C

Why is the post hoc method that Schnall, Benton, & Harvey (2008) Sinnott-Armstrong et al. (2010) use unreliable?

Anna B

Could you explain more why post-hoc isn’t a good method? It isn’t clear to me why this isn’t a good method.

Emilie H

I don't see how the post-hoc prediction really jeopardises the evidence for the hypothesis.

The Tale of the Loaded Die

I predict that they are weighted to N. Then we roll.

vs

We roll. Then I retrodict that they are weighted to whatever number appears most often.

Emilie H

Showing that there is some evidence that the postdiction [...] is confirmed, should weigh in favour of the hypothesis?

Anna B

Suppose you found evidence for something post hoc and then created a new hypothesis and another experiment to check whether this is true would this be an acceptable method?

Marta

What is the difference between biases and heuristics?

They seem similar in that they are both kinds of a mental shortcut that enables us to make quicker judgements.

To use a heuristic (Steve’s df) is to track one attribute by computing another.

I have a bias towards accepting claims that accord with my political views, in part because of the ease-of-processing heuristic.

ease-of-processing heuristic: track the truth of a proposition by computing how easy it is for me to process it.

Jagoda

about Eskine, Kacinik, & Prinz (2011)

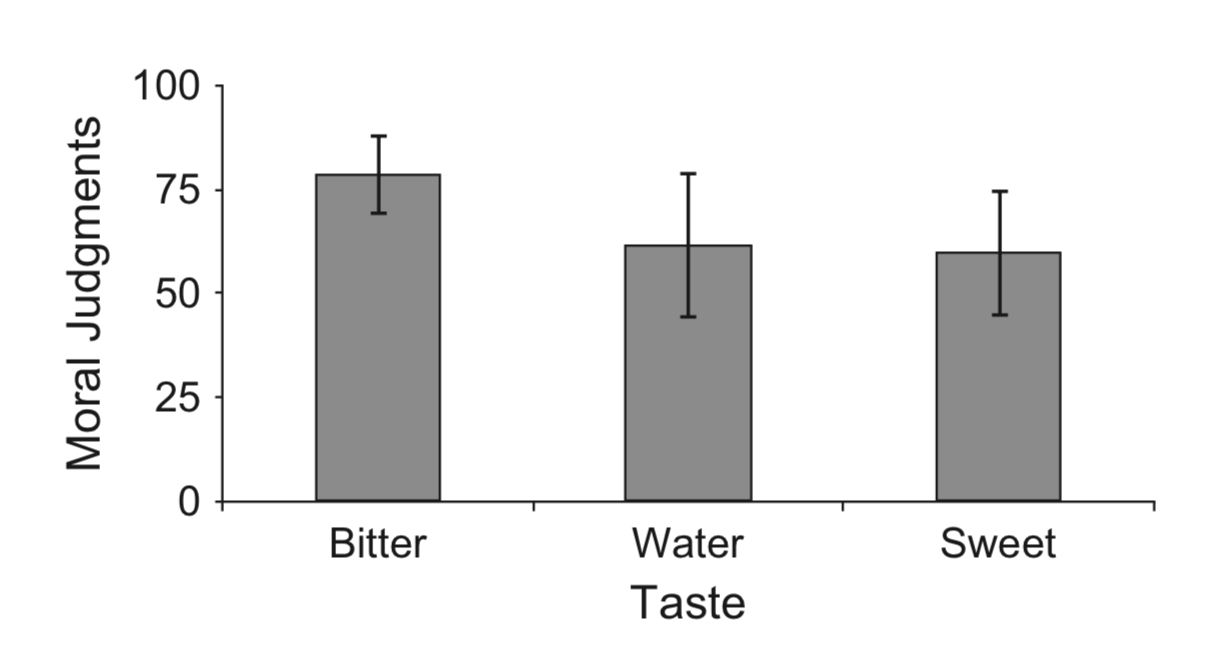

Eskine et al, 2011 figure 1

Jagoda

about Eskine et al. (2011)

How can something such as taste be used to affect moral judgement since the liking of a particular taste itself is a judgement?

For example, if a participant enjoyed the bitter drink they may not necessarily perform in the same way as another participant who did not enjoy the bitter drink.

The hypothesis that some participants enjoyed the bitter drink implies that they did not feel disgust.

It generates the prediction that Eskine et al. (2011) should find no, or only a diminished, effect of bitterness on moral judgements.

Svenja

It seems to me that using the affect heuristic to explain how moral intuitions arise is not sufficient, because then the question arises how the emotions arise.

Do Sinnott-Armstrong et al. (2010), or anybody else, have an explanation for why certain actions trigger certain emotions in us?

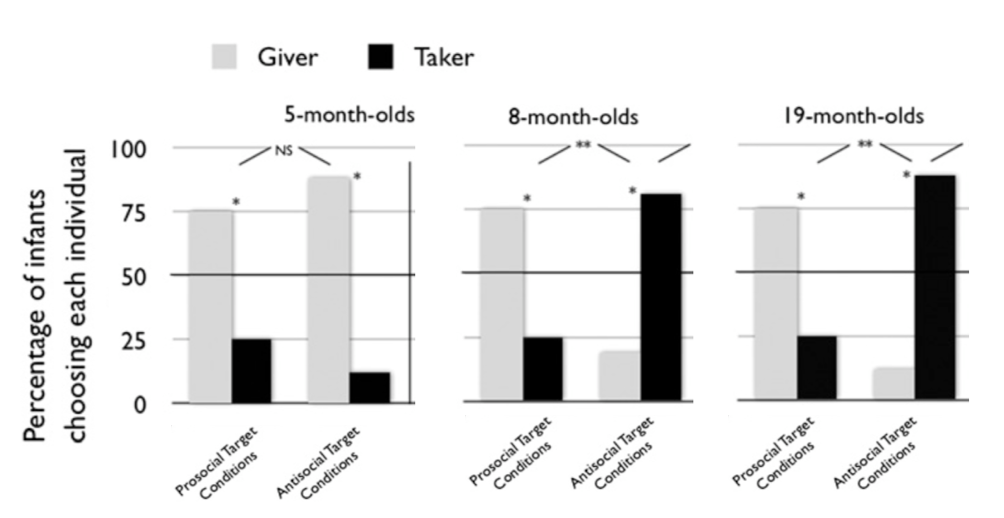

Hamlin et al, 2011 figure 1 (part)

Svenja

It seems to me that using the affect heuristic to explain how moral intuitions arise is not sufficient, because then the question arises how the emotions arise.

Do Sinnott-Armstrong et al. (2010), or anybody else, have an explanation for why certain actions trigger certain emotions in us?

Svenja’s second question

When we talk about an action having the ‘attribute of moral wrongness’ and this attribute being accessible to us or not, are we assuming that such an attribute exists independently of us and that whether or not an action has this attribute is an objective fact?

I’m not sure. Compare the attribute of being blue.

- measurable perceptual divergence even among monolingual speakers of a language with a word for it

- some people do not perceive it at all, so we can talk about this attribute being inaccessible

- we can talk about a thing having the attribute of blueness

Nikki

Can you explain a bit more about how we could distinguish the judgement from the action, since the action in most experiments we've looked at is the act of judging itself (filling in questionnaires)?

Two sources:

- studies that contrast making a hypothetical judgement vs acting with consequences (Gold, Pulford, & Colman, 2015).

- studies that measure changes as how much participants put in a recycling bin each week (Kidwell et al., 2013).