Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Singer vs Kamm on Distance

[email protected]

‘the whole way we look at moral issues---our moral conceptual scheme---needs to be altered’

(Singer, 1972, p. 230).

‘if I am walking past a shallow pond and see a child drowning in it, I ought to wade in and pull the child out [...] It makes no moral difference whether the person I can help is a neighbor's child ten yards from me or a Bengali whose name I shall never know, ten thousand miles away’

(Singer, 1972, pp. 231--2).

Near Alone

I am walking past a pond in a foreign country that I am visiting.

I alone see many children drowning in it, and I alone can save one of them.

To save the one, I must put the $500 I have in my pocket into a machine that then triggers (via electric current) rescue machinery that will certainly scoop him out’ (Kamm, 2008, p. 348)

Far Alone

I alone know that in a distant part of a foreign country that I am visiting, many children are drowning, and I alone can save one of them.

To save the one, all I must do is put the $500 I carry in my pocket into a machine that then triggers (via electric current) rescue machinery that will certainly scoop him out’ (Kamm, 2008, p. 348)

‘the whole way we look at moral issues---our moral conceptual scheme---needs to be altered’

(Singer, 1972, p. 230).

1. On reflection, many people judge that not acting in Near Alone is worse than not Acting in Far Alone.

2. The difference in judgements is due to the difference in distance between the agent and the victim.

3. The difference in distance is not morally relevant.

4. Therefore, it is possible to be convinced that there is a morally relevant difference between scenarios even when there is not.

distance ‘can alter our obligation to aid.’

(Kamm, 2008, p. 368)

[1] ‘when we think we have a strong obligation to aid in the Near Alone Case and not in the Far Alone Case, it is the difference in distance [...] that is determinative of the sense of obligation’

(Kamm, 2008, p. 357).

[2] ‘one has a moral prerogative to give greater weight to one’s own interests’

If you use this prerogative, then ‘there is also a duty [...] to take care of what is associated with [you], for example, the area near [you]’

‘the whole way we look at moral issues---our moral conceptual scheme---needs to be altered’

(Singer, 1972, p. 230).

1. On reflection, many people judge that not acting in Near Alone is worse than not Acting in Far Alone.

2. The difference in judgements is due to the difference in distance between the agent and the victim.

3. The difference in distance is not morally relevant.

4. Therefore, it is possible to be convinced that there is a morally relevant difference between scenarios even when there is not.

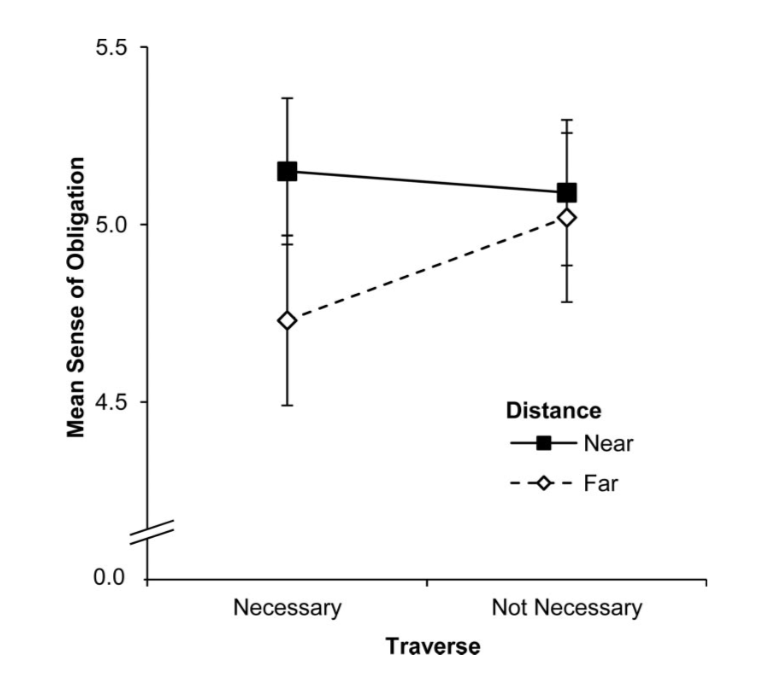

J. Nagel & Waldmann (2013, p. figure 3)

Near Alone

I am walking past a pond in a foreign country that I am visiting.

I alone see many children drowning in it, and I alone can save one of them.

To save the one, I must put the $500 I have in my pocket into a machine that then triggers (via electric current) rescue machinery that will certainly scoop him out’ (Kamm, 2008, p. 348)

Far Alone

I alone know that in a distant part of a foreign country that I am visiting, many children are drowning, and I alone can save one of them.

To save the one, all I must do is put the $500 I carry in my pocket into a machine that then triggers (via electric current) rescue machinery that will certainly scoop him out’ (Kamm, 2008, p. 348)

‘people might indeed share Kamm’s (2007) intuition that her Near Alone and Far Alone cases differ slightly in the degree of moral obligation they imply. [...]

this difference is not attributable to distance per se

Rather, the difference can be traced back to a confounded factor, namely informational directness

At constant levels of directness, distance ceases to be of moral relevance to people’

(J. Nagel & Waldmann, 2013, p. 243).

‘the whole way we look at moral issues---our moral conceptual scheme---needs to be altered’

(Singer, 1972, p. 230).

1. On reflection, many people judge that not acting in Near Alone is worse than not Acting in Far Alone.

2. The difference in judgements is due to the difference in distance between the agent and the victim.

3. The difference in distance is not morally relevant.

4. Therefore, it is possible to be convinced that there is a morally relevant difference between scenarios even when there is not.

‘It may be suggested that proximity matters as a heuristic device that correlates with morally significant factors, though it itself is not morally significant. [...] But *I doubt that* these factors explain the apparent moral significance of distance’ (Kamm, 2008, p. 379, my emphasis).

distance ‘can alter our obligation to aid.’

(Kamm, 2008, p. 368)

[1] ‘when we think we have a strong obligation to aid in the Near Alone Case and not in the Far Alone Case, it is the difference in distance [...] that is determinative of the sense of obligation’

(Kamm, 2008, p. 357).

[2] ‘one has a moral prerogative to give greater weight to one’s own interests’

If you use this prerogative, then ‘there is also a duty [...] to take care of what is associated with [you], for example, the area near [you]’

Could scientific discoveries undermine, or support, ethical principles?

Yes, unless Kamm (2008)’s broad approach is misguided.