Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

What Is the Role of Fast Processes In Not-Justified-Inferentially Judgements?

[email protected]

Heider & Simmel (1944) (redrawn)

What Is the Role of Fast Processes In Not-Justified-Inferentially Judgements?

[email protected]

What Is the Role of Fast Processes In Not-Justified-Inferentially Judgements?

[email protected]

Heider & Simmel (1944) (redrawn)

1. Ethical judgements are explained by a dual-process theory, which distinguishes faster from slower processes.

2. Faster processes are unreliable in unfamiliar* situations.

3. Therefore, we should not rely on faster process in unfamiliar* situations.

4. When philosophers rely on not-justified-inferentially premises, they are relying on faster processes.

5. We have reason to suspect that the moral scenarios and principles philosophers consider are unfamiliar situations.

6. Therefore, not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios, and debatable principles, cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.

Objection: Research on fast processes is not relevant because philosophers considering moral scenarios are thinking very slowly about them.

Observation: Physicists in the Aristotelian tradition were also thinking very slowly about physical scenarios (e.g. those involving the behaviours of objects launched vertically).

Yet their judgements reflect, and relied on, fast processes. (There is no way they could have arrived at the judgements they did if not for the operations of fast processes.)

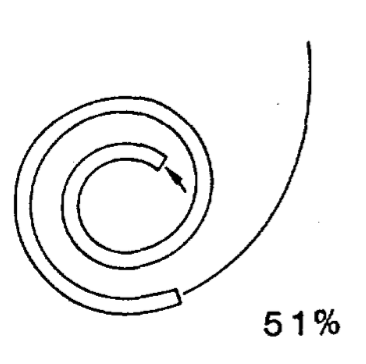

McCloskey, Caramazza, & Green (1980, p. figure 2D)

why?

because fast processes make it appear so

(Kozhevnikov & Hegarty, 2001)

Objection: Research on fast processes is not relevant because philosophers considering moral scenarios are thinking very slowly about them.

Observation: Physicists in the Aristotelian tradition were also thinking very slowly about physical scenarios (e.g. those involving the behaviours of objects launched vertically).

Yet their judgements reflect, and relied on, fast processes. (There is no way they could have arrived at the judgements they did if not for the operations of fast processes.)

So does the fast process directly influence the slow judgement?

No. (Or not significantly.)

fast process -> appearance + high subjective confidence

reflection on appearance -> slow judgement

The fast process provides phenomenal material for slow judgement.

But why accept that this is also how

not-justified-inferentially ethical judgements work?

When philosophers rely on not-justified-inferentially premises, are the relying on faster processes?

No. Philosophers are magic.

Yes. Philosophers are like everyone else.

There’s nothing else but the faster processes that could give rise to not-justified-inferentially judgements.

1. Ethical judgements are explained by a dual-process theory, which distinguishes faster from slower processes.

2. Faster processes are unreliable in unfamiliar* situations.

3. Therefore, we should not rely on faster process in unfamiliar* situations.

4. When philosophers rely on not-justified-inferentially premises, they are relying on faster processes.

5. We have reason to suspect that the moral scenarios and principles philosophers consider are unfamiliar situations.

6. Therefore, not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios, and debatable principles, cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.