Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Evidence for Dual Process Theories

[email protected]

1. Ethical judgements are explained by a dual-process theory, which distinguishes faster from slower processes.

2. Faster processes are unreliable in unfamiliar* situations.

3. Therefore, we should not rely on faster process in unfamiliar* situations.

4. When philosophers rely on not-justified-inferentially premises, they are relying on faster processes.

5. We have reason to suspect that the moral scenarios and principles philosophers consider are unfamiliar situations.

6. Therefore, not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios, and debatable principles, cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.

Evidence Greene (2014) cites includes:

- Suter & Hertwig (2011)

- Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

- Conway & Gawronski (2013)

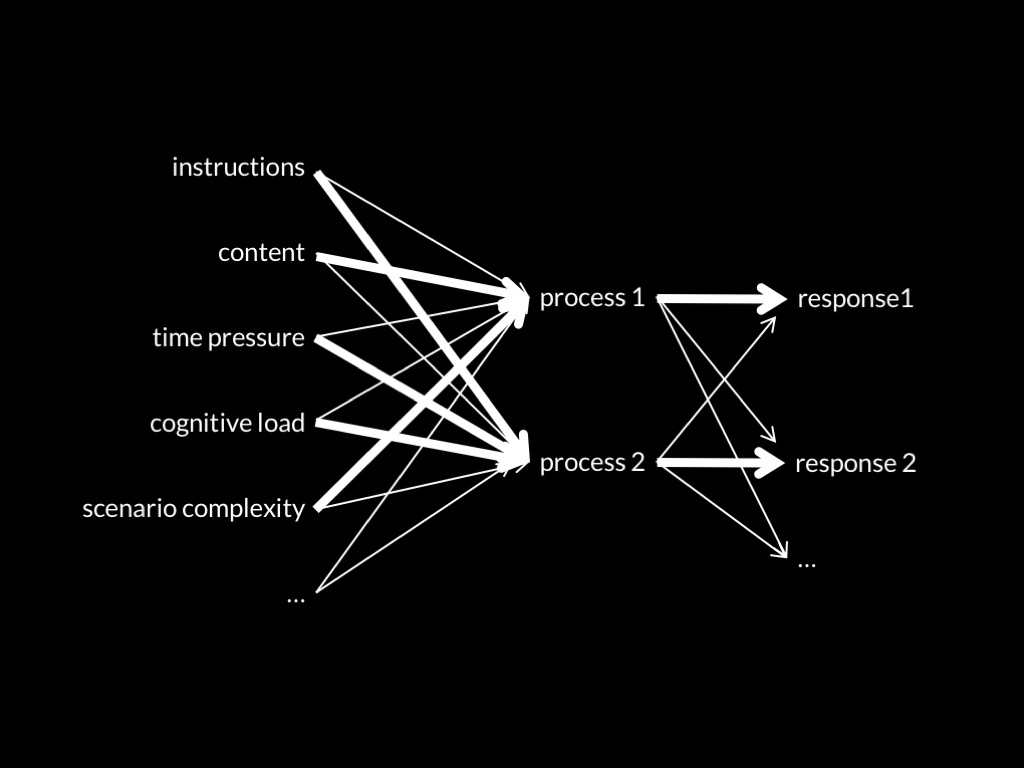

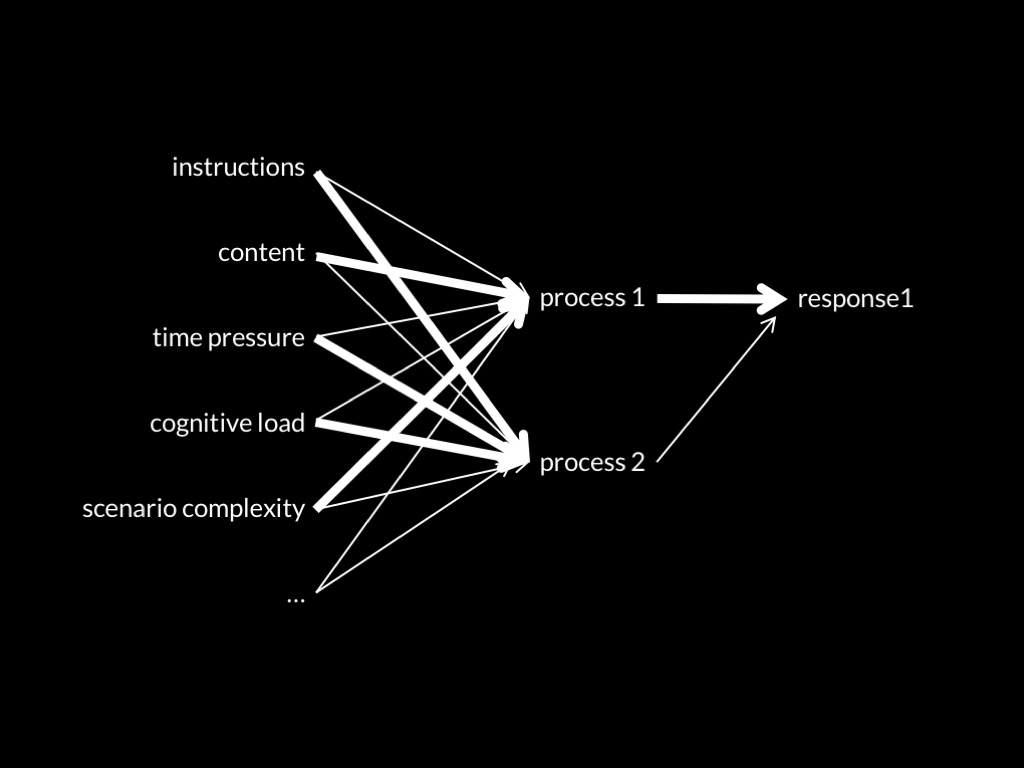

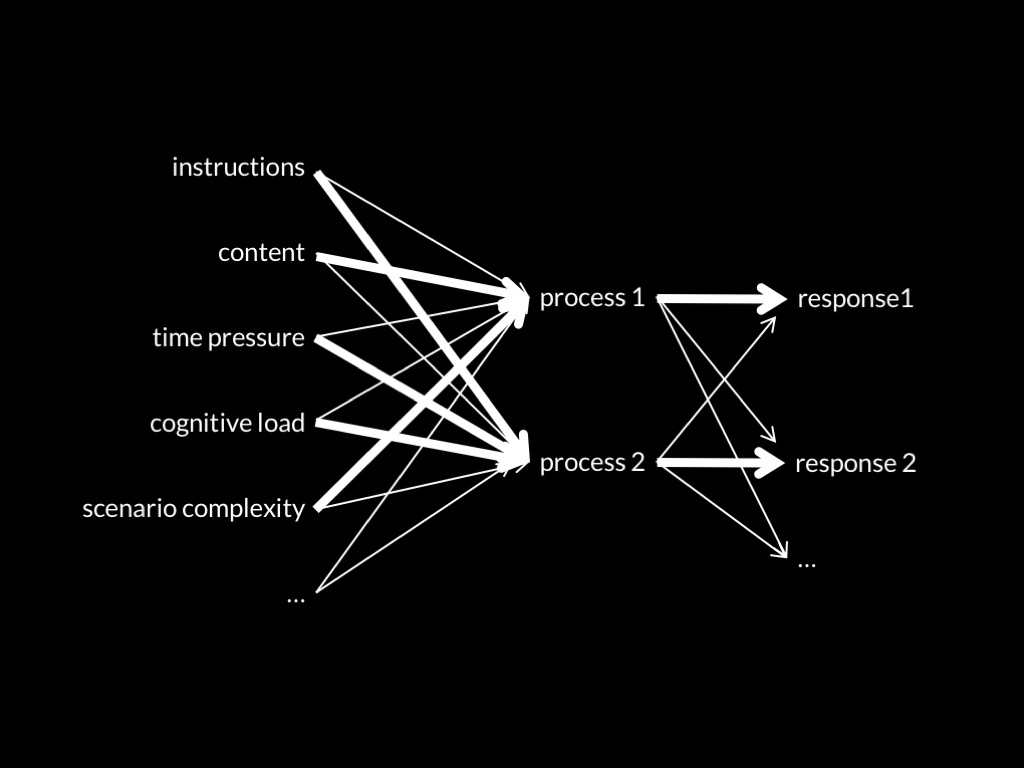

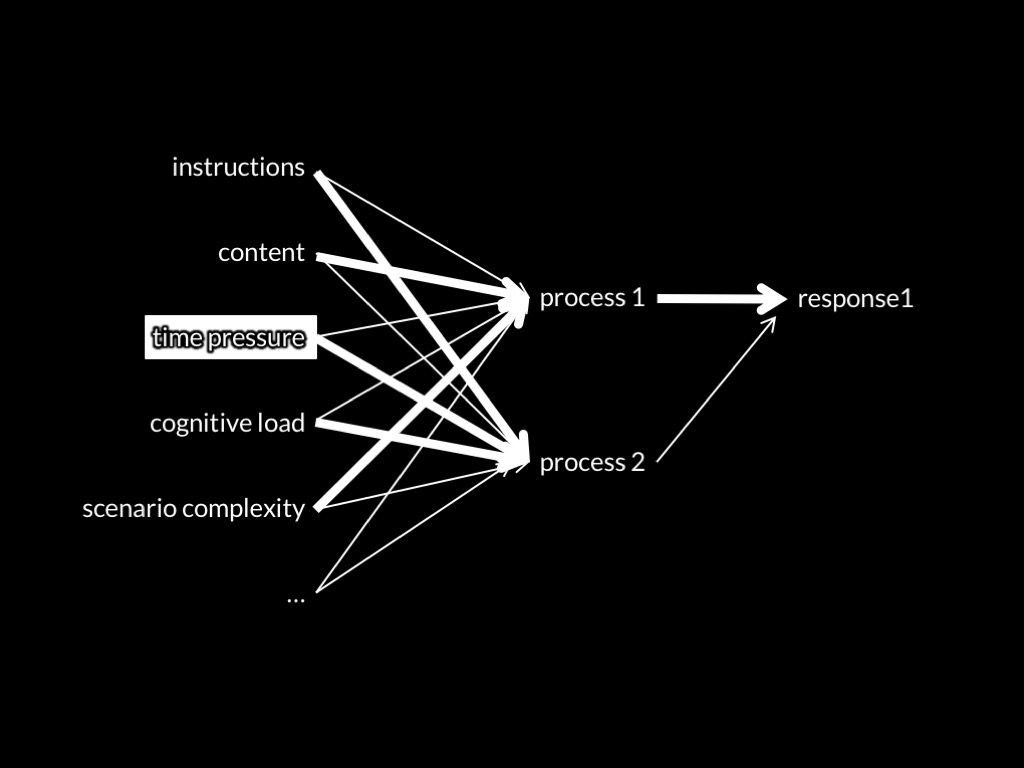

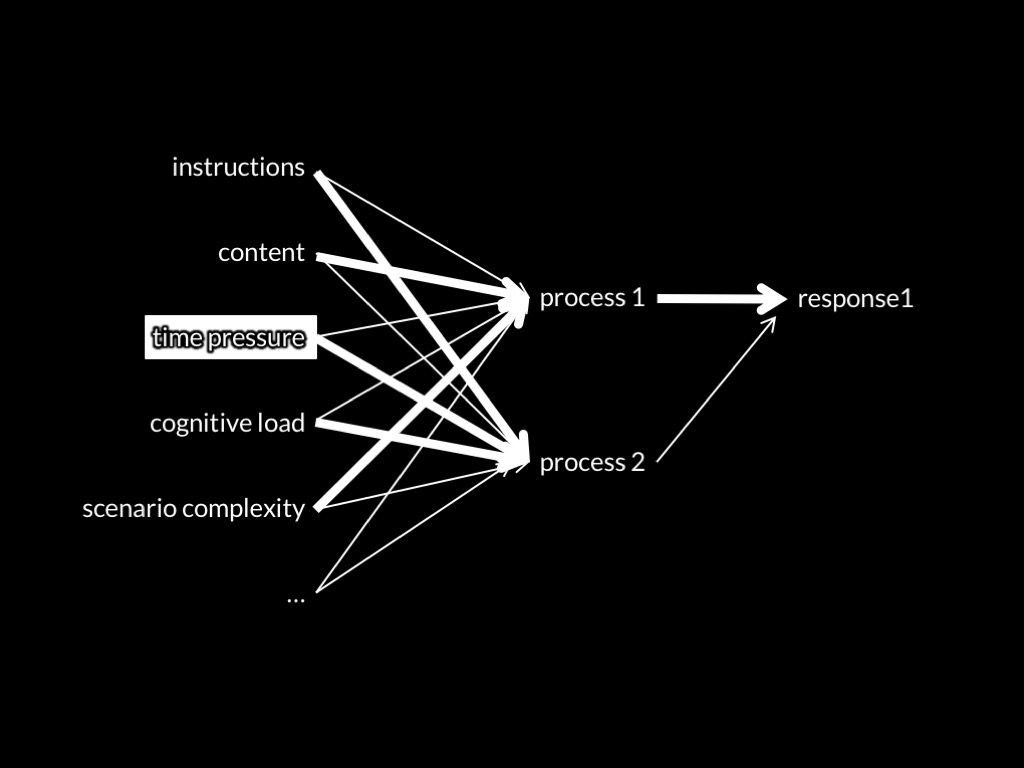

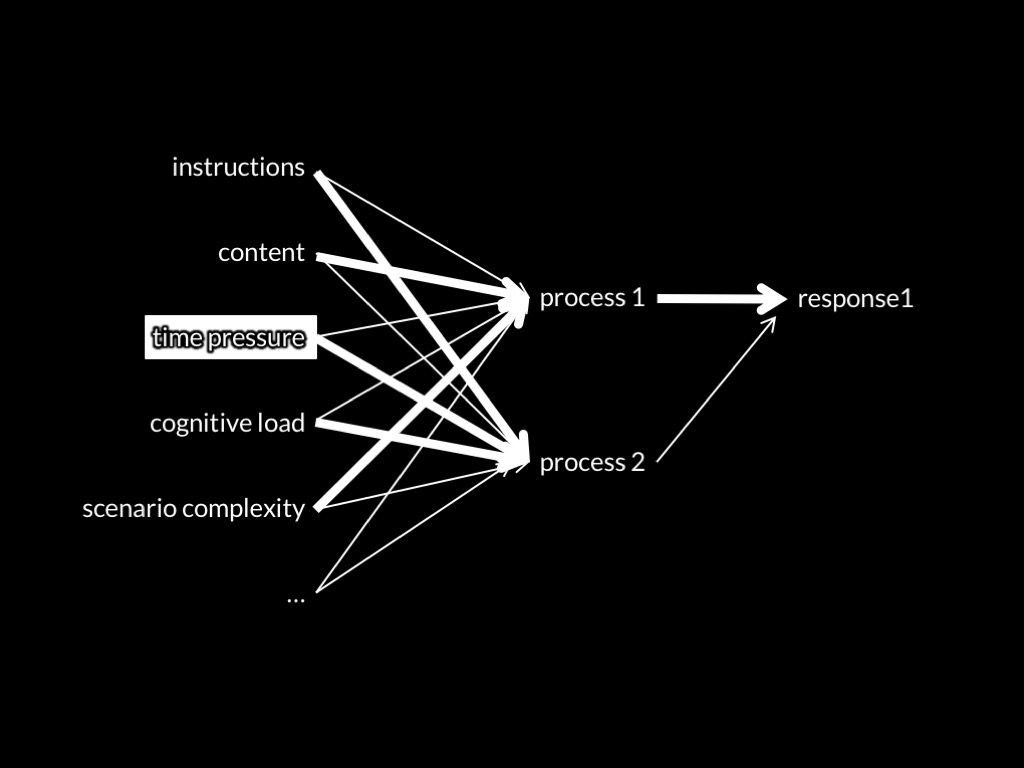

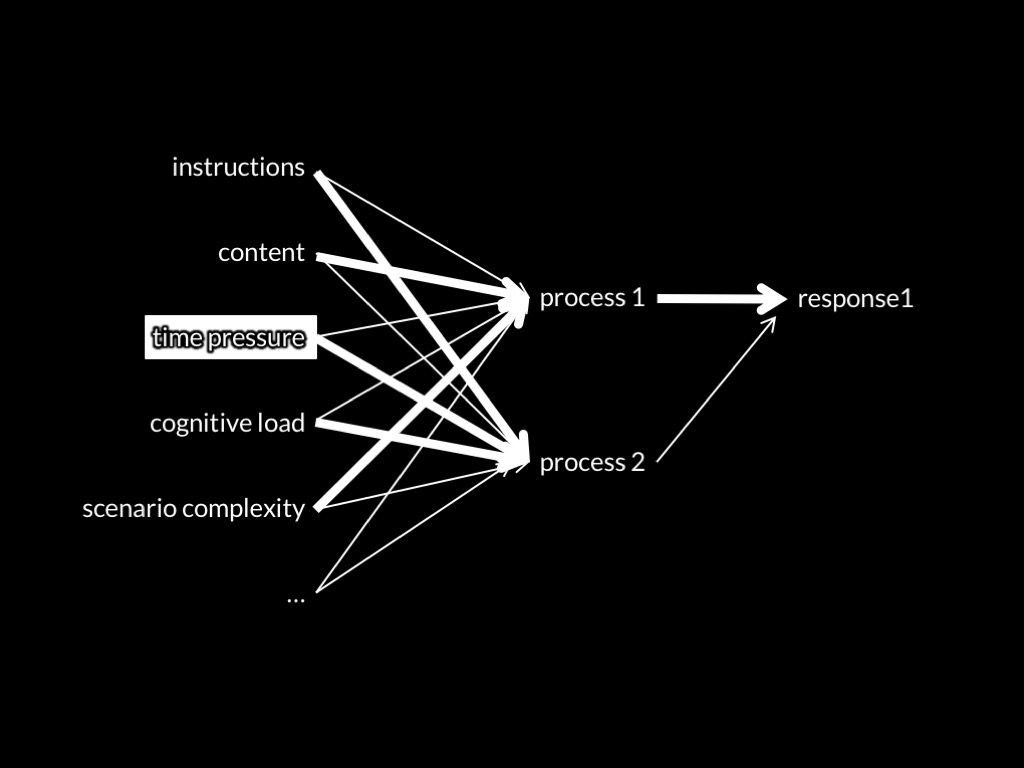

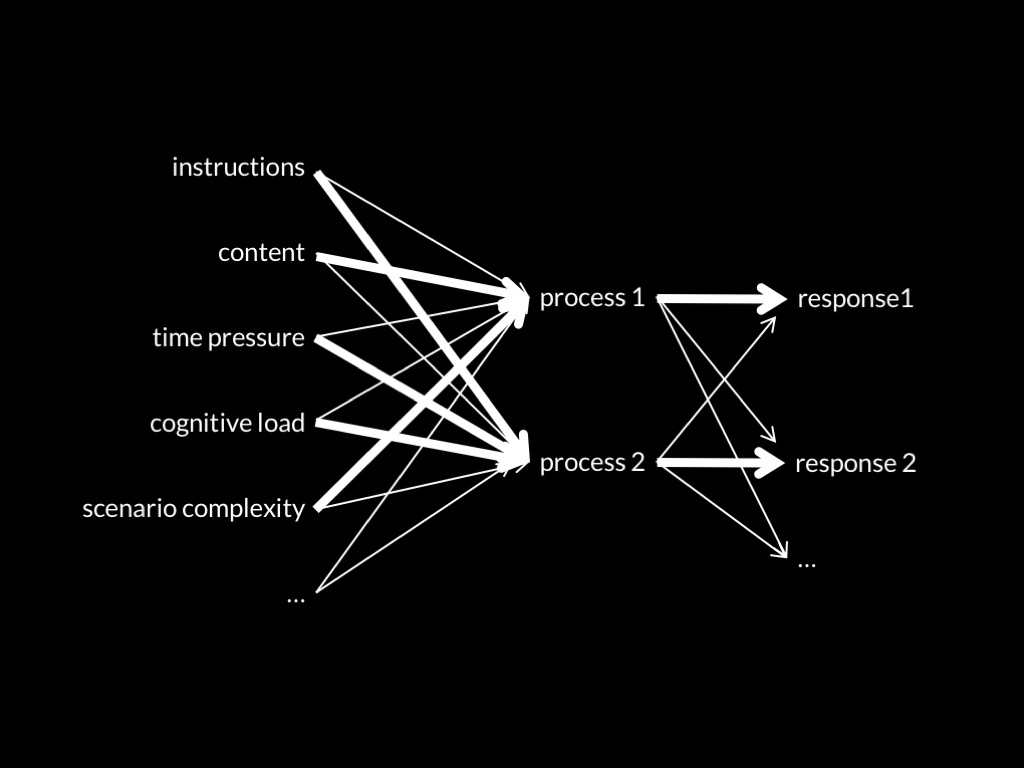

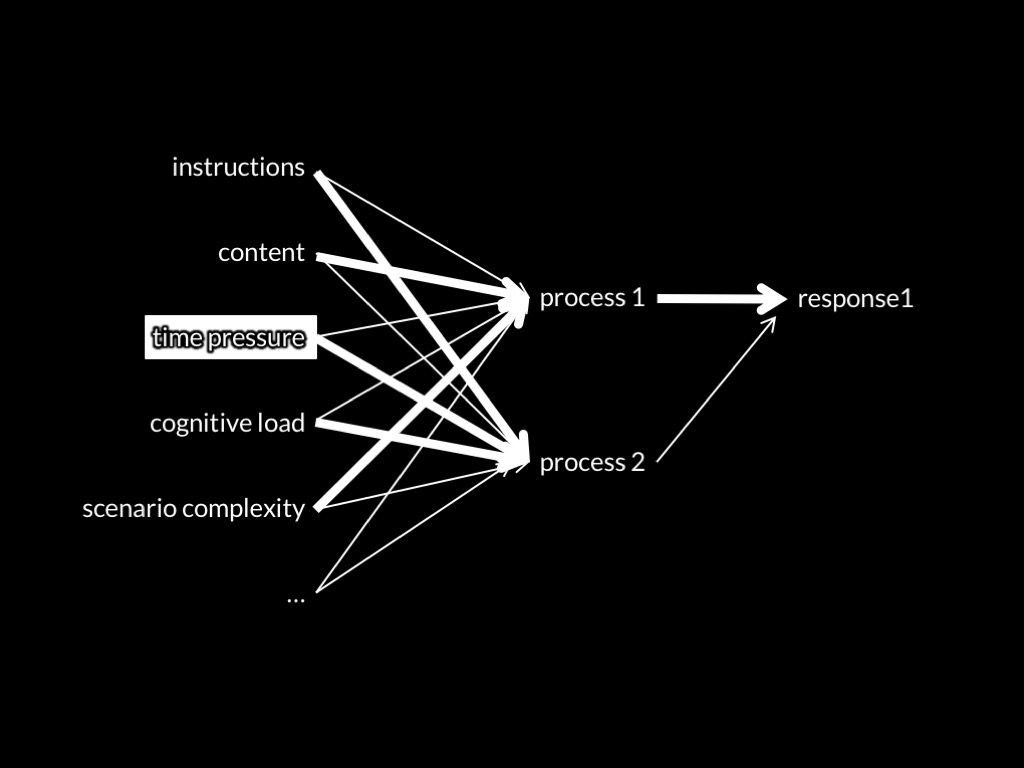

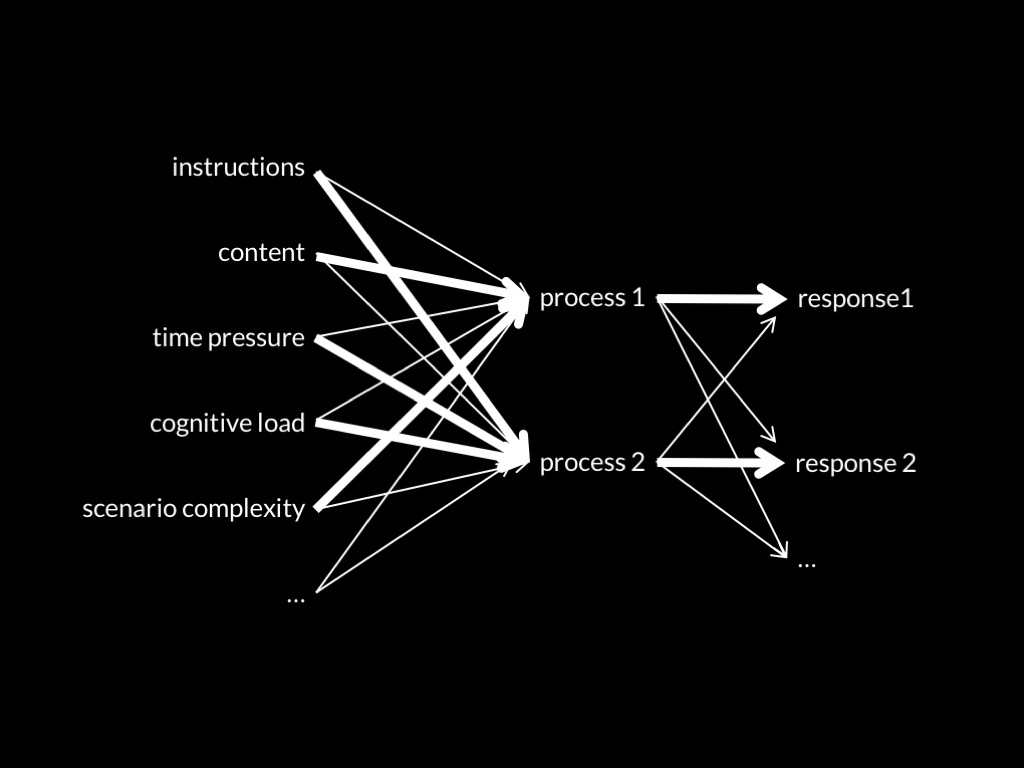

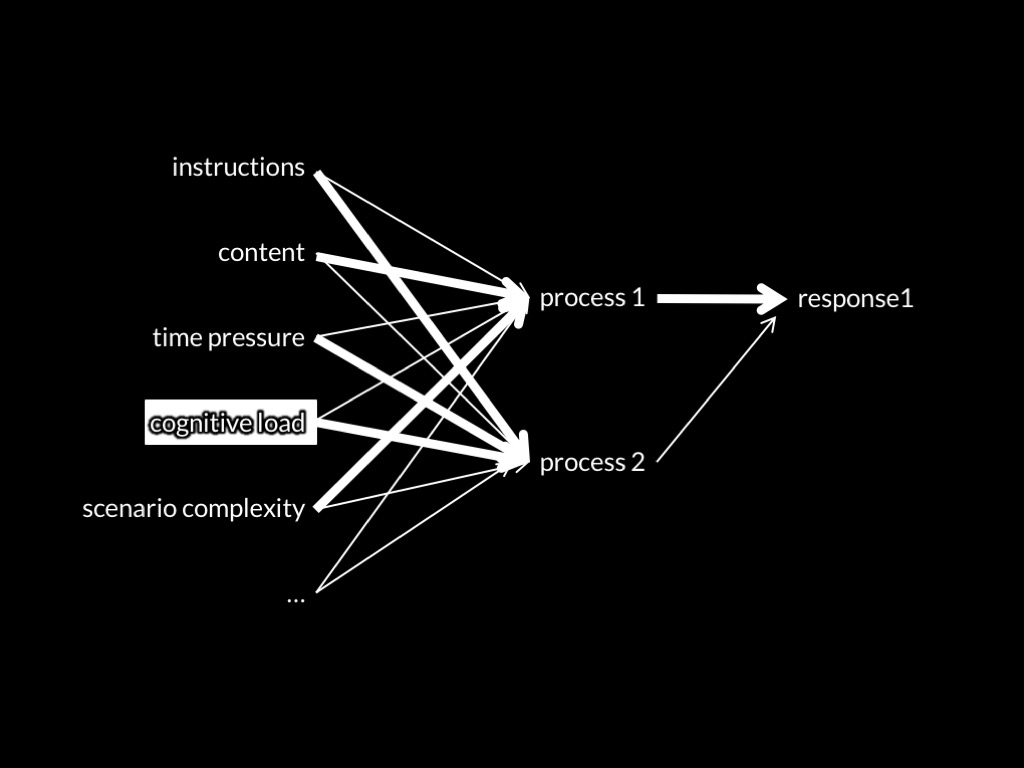

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

Prediction 1: limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce the influence of distal outcomes.

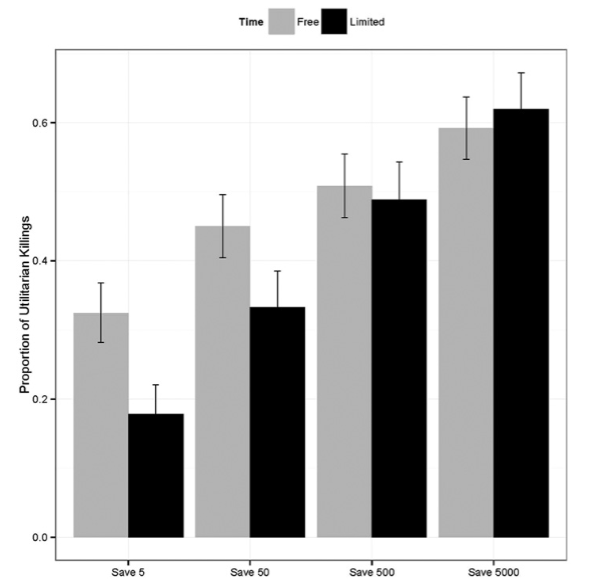

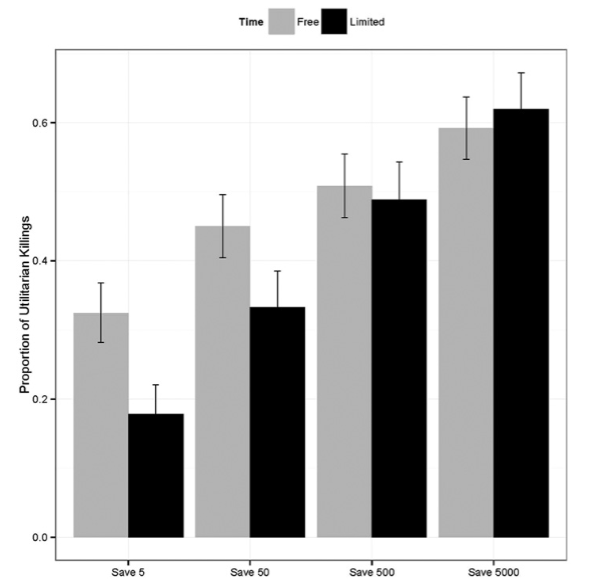

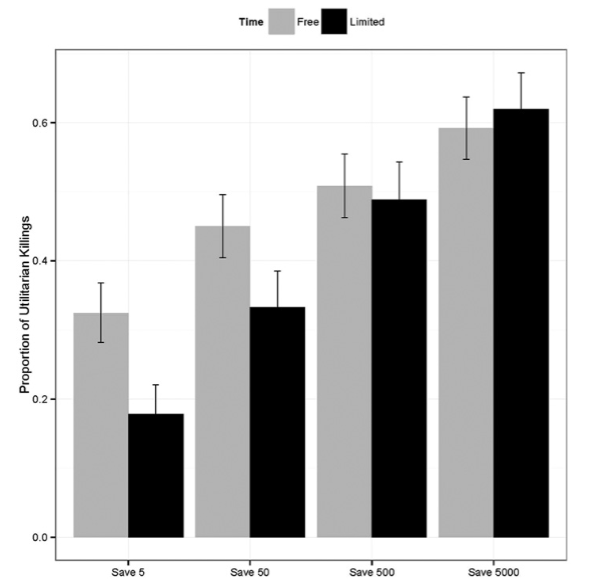

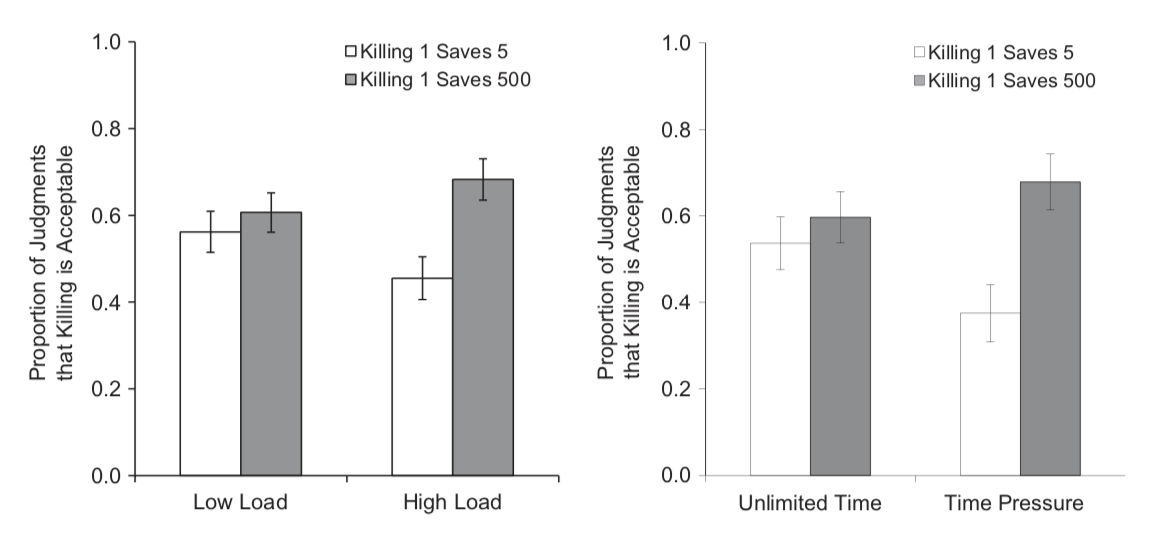

Suter & Hertwig, 2011 figure 1

‘participants in the time-pressure condition, relative to the no-time-pressure condition, were more likely to give ‘‘no’’ responses in high-conflict dilemmas’

Good start.

But it would be even better if the outcomes were varied.

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

Prediction 1: higher cognitive load will reduce the influence of distal outcomes.

Evidence Greene (2014) cites includes:

- Suter & Hertwig (2011)

- Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

- Conway & Gawronski (2013)

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

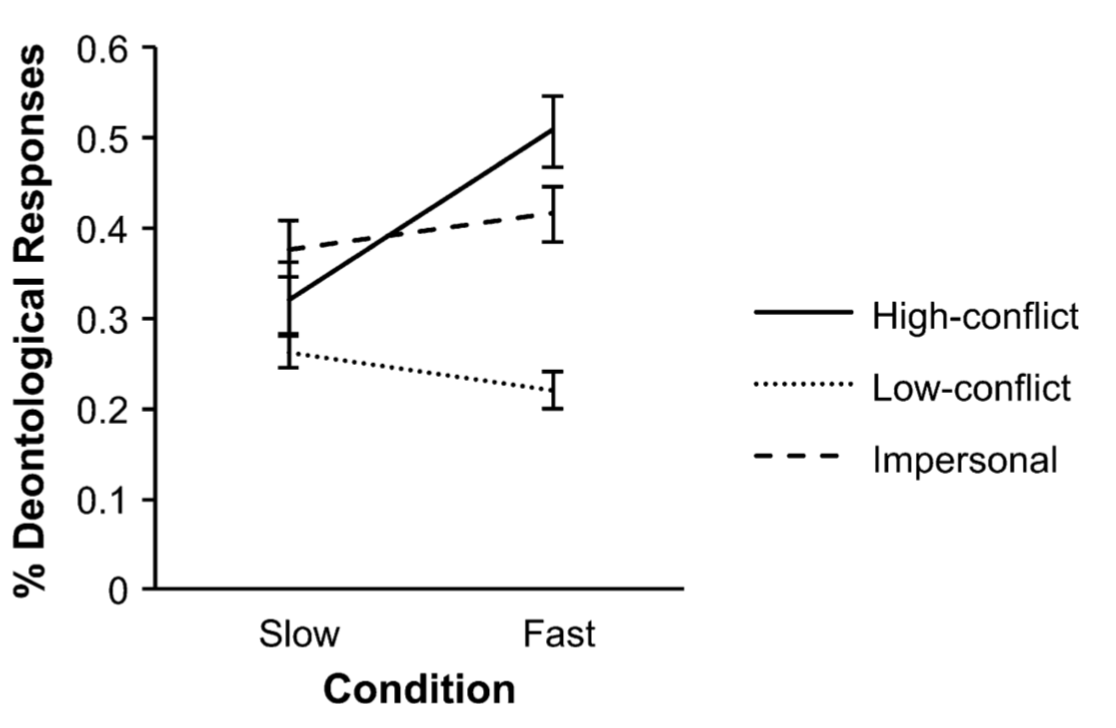

Prediction 2: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce consequentialist responses.

Trémolière and Bonnefon, 2014 figure 4

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

Prediction 2: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce consequentialist responses.

Prediction 2*: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce sensitivity to outcomes.

Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014, p. figure 4)

Prediction 2*: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce sensitivity to outcomes.

Gawronski & Beer (2017, p. figure 1); data from Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

Prediction 2*: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce sensitivity to outcomes.

Evidence Greene (2014) cites includes:

- Suter & Hertwig (2011)

- Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

- Conway & Gawronski (2013)

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

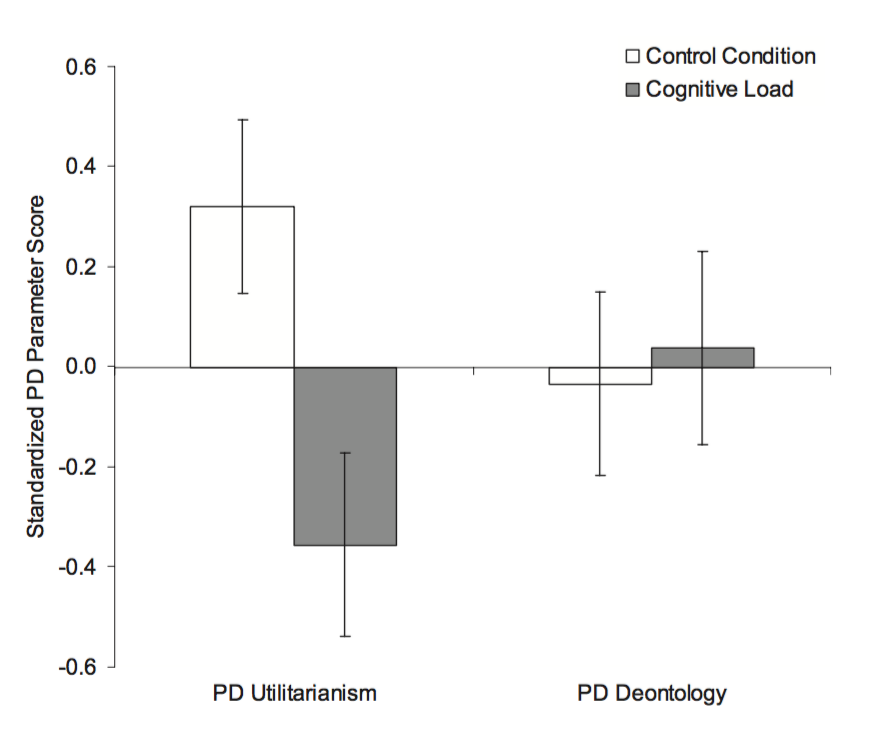

Prediction 3: higher cognitive load will reduce the dominance of the more outcome-sensitive process.

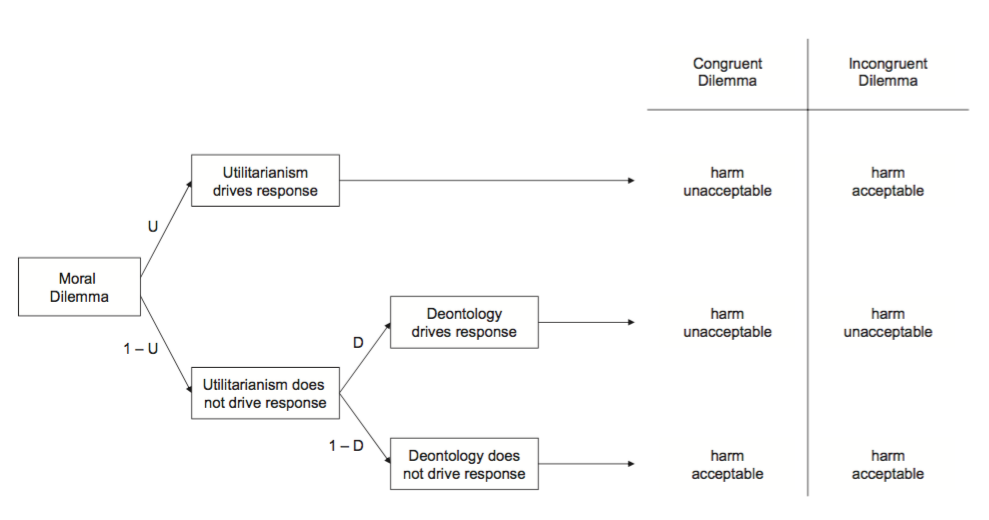

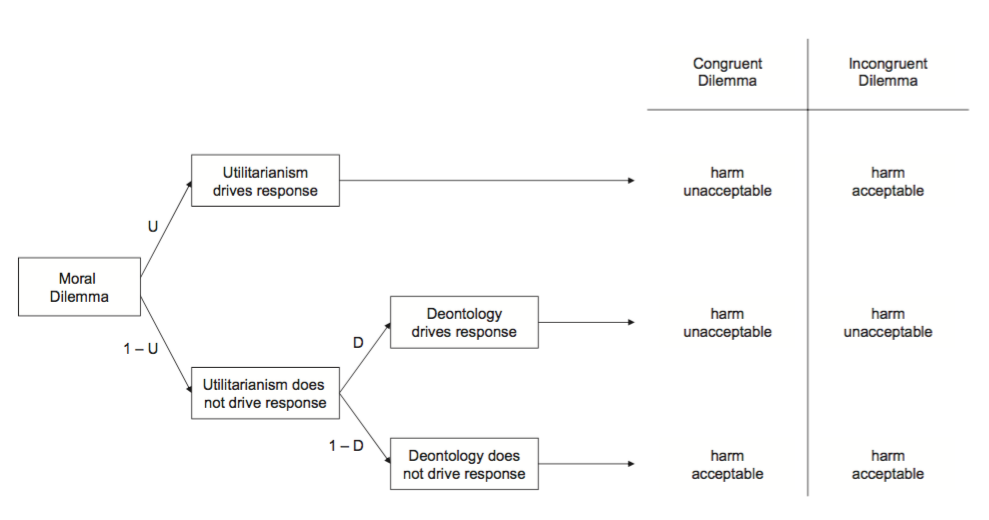

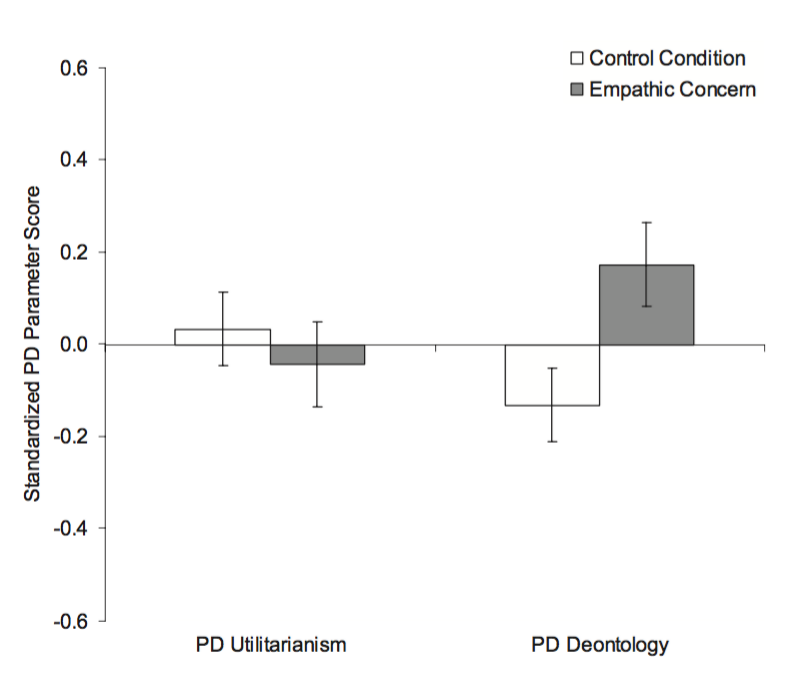

Conway & Gawronsky 2013, figure 1

Conway & Gawronsky 2013, figure 3

Evidence Greene (2014) cites includes:

- Suter & Hertwig (2011)

- Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

- Conway & Gawronski (2013)

1. Ethical judgements are explained by a dual-process theory, which distinguishes faster from slower processes.

2. Faster processes are unreliable in unfamiliar* situations.

3. Therefore, we should not rely on faster process in unfamiliar* situations.

4. When philosophers rely on not-justified-inferentially premises, they are relying on faster processes.

5. We have reason to suspect that the moral scenarios and principles philosophers consider are unfamiliar situations.

6. Therefore, not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios, and debatable principles, cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.

evidence against?

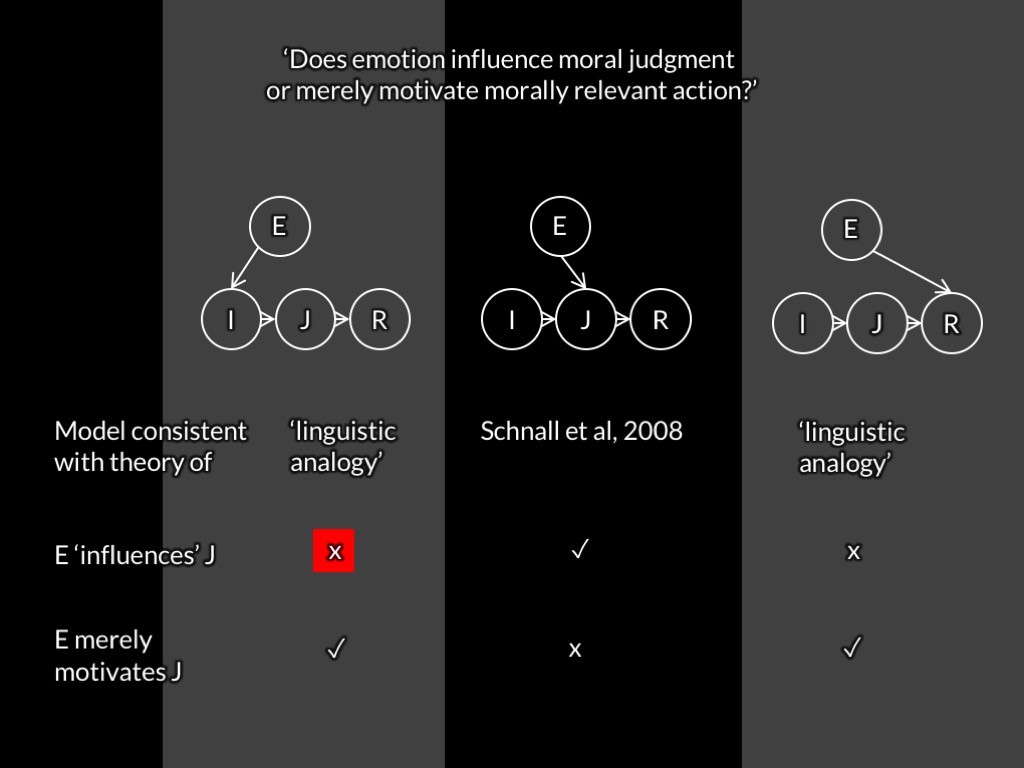

p.s. role of emotion

‘we exposed half of the participants in Study 3 to a photograph of the victim who would be harmed in case participants judge harmful action as acceptable.

The rationale for this manipulation was that photographs identify victims, thereby evoking increased empathy and more emotional distress’

(Conway & Gawronski, 2013, p. 226)

prediction: higher empathy will increase the dominance of the less consequentialist process

Conway & Gawronsky 2013, figure 3